“My poor, un-white thing! Weep not nor rage. I know, too well, that the curse of God lies heavy on you. Why? That is not for me to say, but be brave! Do your work in your lowly sphere, praying the good Lord that into heaven above, where all is love, you may, one day, be born – white!” (Du Bois 18)

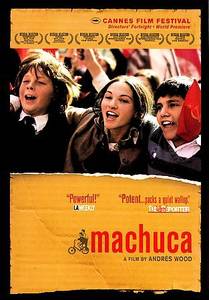

Near the midpoint of the diegesis of Andrés Wood’s film entitled Machuca (2004), we witness to an emotive scene between three young Chilean friends in close-up (or what Gilles Deleuze in Cinema 1 fittingly terms the affection-image) — a cinematographic decision typical of the film. In this lust-filled moment, teenagers Gonzalo Infante (Matías Quer) and Pedro Machuca (Ariel Mateluna) share kisses full of condensed milk with their female friend Silvana (Manuela Martelli). Gonzalo – the only fair-skinned and bourgeoisie member in the troika – received the condensed milk as a part of his family’s rations. Such allotments were not even available to his two impoverished friends during Chile’s food shortage. Yet, in this scene, Andrés Wood is showing us more than just three youths exploring their sexuality as their milk and saliva amalgamate. Instead, the talented Chilean director is showing us the raison d’être of his film: economic and social divisions are learned realities; altruistic and caring behaviors are what come naturally. At the fons et origo of the film, these young characters instinctively overcome socioeconomic and color differences. But, instead of encouraging friendship across lattices of class and ethnicity, the Chilean society around them works throughout the film to tear their relationship asunder.

The film, set in 1973, provides a fictional account of the tensions preceding the military coup d’état. Shortly thereafter, Augusto Pinochet would ensure that “military rule became entrenched” as he seized power in the country, eventually becoming a military president in Chile (Constable and Valenzuela 62). The three child actors in Machuca deliver absolutely heart-wrenching performances; they exude the tenderness and naivety of three youths who do not understand the abnormal nature of their friendship. In fact, their ignorance is what catalyzes much of the film.

Gonzalo meets Pedro when he is accepted to Saint Patrick’s School on a grant for impoverished students created by socially conscious priests. The boys quickly find themselves drawn together as outcasts; Pedro lives in a shantytown and is likely of indigenous ancestry while Gonzalo’s intelligence causes him to be harassed by other students. After Gonzalo and Pedro are both attacked by the school’s bullies, the schoolboys begin to feel a sense of camaraderie for one another. It also doesn’t hurt that Gonzalo is attracted to Pedro’s neighbor Silvana – a headstrong girl who was compelled to drop out of school when her mother abandoned her family.

Soon enough, the youths begin to spend more time together. Gonzalo and Pedro share shoes and books. Gonzalo goes to Pedro and Silvana’s destitute community near the Mapocho River and there this privileged youth even attends a rally in support of socialist President Salvador Allende. At this populist congregation, the three teenagers begin to jump together in solidarity to show that they aren’t fascist “mummies.” However, as the friendship between Pedro and Gonzalo continues to blossom it simultaneously begins to encounter opposition from their respective classes. The boyfriend of Gonzalo’s sister, a member of the fascist group called Fatherland and Liberty, mocks Pedro for his impoverished lifestyle and for his surname – Machuca – and then tries to intimidate him with a nunchaku (nunchucks). Likewise, Pedro’s father virulently predicts that Gonzalo will lead a comfortable lifestyle with Pedro as his janitor. Even their school is in a maelstrom when the families of affluent students become outraged at the grants that insolvent students have received. These tensions finally culminate near the film’s denouement when Silvana gets into a physical confrontation with Gonzalo’s mother (Aline Kuppenheim) at a political rally. Silvana and Pedro flee the scene in terror and the camera’s focus goes soft as we observe the mother’s disdain for these children. In this moment, spectators understand that Gonzalo must pick a side.

Throughout the course of the film, the audience witnesses the onscreen manifestation of the thesis held by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino about the impacts of neocolonialism in their famed essay “Towards a Third Cinema:” “In order to impose itself, neocolonialism needs to convince the people of a dependent country of their own inferiority…If you want to be a man, says the oppressor, you have to be like me…deny your own being, transform yourself into me” (Solanas and Getino). In Machuca, we see one character of privilege – Gonzalo – forced to accept the inferiority of his fellow Chileans and reaffirm his status as superior. He is forced to highlight his fair skin – his privilege – to the military in order to escape from the shantytown turned war zone after the coup. The reclusive town is immediately targeted because of its support for President Allende. In a manner reminiscent of the words of Du Bois, we might even go as far as to suggest that at the end of the film, Gonzalo learns to become white. “Look at me,” Gonzalo screams at a soldier who attempts to detain him. Gonzalo learns to accept that his skin and his financial status provide him sanctimonious access to the very systems by which Pedro and Silvana are oppressed. Obviously at this point, the trio then undergoes the social balkanizations that the rest of society had already desired for them. The film closes with a wide-angle shot of Gonzalo staring out at the destroyed shantytown followed by a close-up of him in tears as he, out of focus, walks away from the camera. The audience remains unsure what he is walking away from, his friendships or society’s immoral normalities.

Works Cited

Constable, Pamela and Arturo Valenzuela. A Nation of Enemies: Chile Under Pinochet. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1993. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983. Print.

Du Bois, W.E.B. Voices from Within the Veil. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc. 1920. Print.

Solanas, Fernando, and Octavio Getino. “Towards a Third Cinema.” Documentary Is Never Neutral, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2010. <http://www.documentaryisneverneutral.com/words/camasgun.html>.

Author Biography

Stephen Borunda is a Mexican-American filmmaker and educator currently residing in Santiago de Chile. He graduated from Johns Hopkins with a BA in political science and history and an MS in education. He hopes to synthesize these areas of passion with film by pursuing a PhD in cinema with a concentration on Latin American films in the Southern Cone. He is fascinated by film’s power as a political and educational medium.

Film Details

Machuca (2004)

Chile

Director Andrés Wood

Runtime 121 minutes