One evening after a full day of work, with four tables pushed together at a café in 2013, I first heard of the Stephen King Dollar Babies program during a precursory meeting which would lead to a film festival that friends and I would put together. One of the local filmmakers in the group simply asked if we had heard of Dollar Babies. They would go on to become my favorite programming block for our short-lived festival. At the same time, over a thousand miles away at the Crypticon Horror Con in Minnesota, Anthony Northrup was hosting his First Annual Stephen King Dollar Baby Film Fest (15). For the uninitiated, “Dollar Babies” are short films where King officially grants adaptation rights to student and promising young filmmakers for a single dollar.

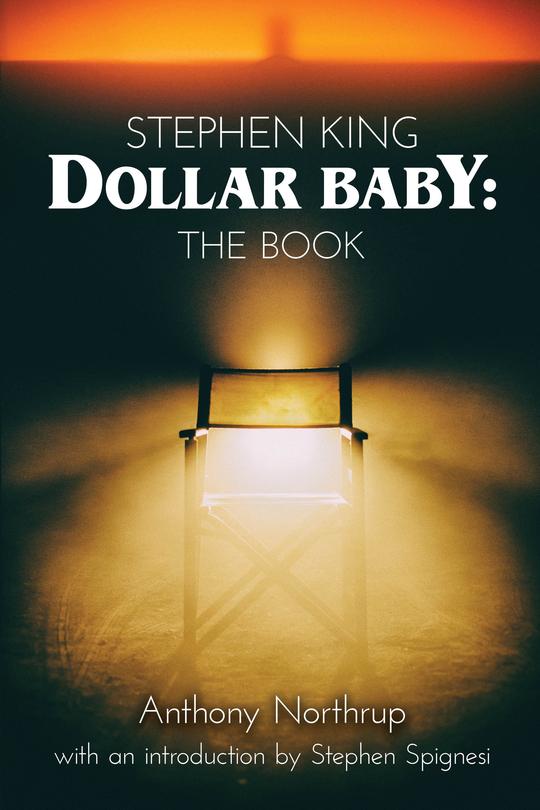

Northrup is an unabashed fan of horror movies and Stephen King, as he acknowledges in his introductory author’s note. That love is evident throughout his exhaustive but ultimately facile tome Stephen King Dollar Baby: The Book. Ultimately, this is a collection of interviews with a subset of filmmakers who have one thing in common: adapting King’s short stories into short films for noncommercial use such as demo reels and film festivals. With every film spotlighted being difficult to see outside of conventions or film festivals, Northrup is asking the reader to experience them through only the biased lens of both the author and filmmaker. It is exasperating to find the movies being written about. In addition, each of the three main parts of the book lacks any sort of logical structure needed to propel a reader through its Möbius strip of redundancies. In spite of the book’s flaws, the subject matter is a fascinating one and its undertaking impressive. Sadly, Stephen King Dollar Baby: The Book does not work without seeing the movies.

Northup’s 560-page book is mainly one of interviews culled from websites and fan pages he’s written for, such as Through the Black Hole and “All Things King” on Facebook. Although there is new material in the more than a hundred preluding pages of interviews with Dollar Baby filmmakers in Part One, the section itself would have benefited from a more streamlined selection of material. Aside from articles on or interviews with well-known directors who worked on Dollar Babies in the past, such as Frank Darabont and Mick Garris, Part One feels like an extension of the introduction, foreword, and author’s note. The book’s hundred pages of essays by “filmmakers, fans, and friends” (31), presuppose that King fandom is a strong enough link between them to warrant space on a bookshelf alongside the oft-talked about The Complete Stephen King Encyclopedia, written by the introduction’s author Stephen Spignesi. Not only does the perceived association appear tangential, but it also becomes tedious. Northrup shuts the door on a much larger audience of film enthusiasts when he claims the “book was written for fans by a fan” (16).

It’s important to remember that these films are noncommercial by design, and in order to track down—or even simply be aware of them, as published writer and King fan Kevin Quigley points out, “you had to know someone” (83). While I’m lucky enough to have seen a handful of the Dollar Babies covered in the book, only a few adaptations were memorable — such as Frank Darabont’s The Woman in the Room (1983), Jay Holben’s Paranoid: A Chant (2000), or Billy Hanson’s Survivor Type (2012). Without rigorous searching, the films are difficult to find online, making festivals the most apparent way of viewing them. While I have had the advantage of attending numerous film festivals, many readers would not. Together with the frustration of being unable to readily rewatch any of the Dollar Babies I first enjoyed years ago, it is easy to see how the book can dishearten a reader unversed in the films (even if an interview sparks their interests). While Quigley affirms “the enjoyment of art should be public” (85), one wonders why there are no contact details included, which could allow readers to reach out to filmmakers and potentially gain access to view the films.

The same frustrations of the readers who cannot see these films are echoed in the book’s structure. Complicated by arguable decisions in its organization, the chronology of interviews in the book was particularly problematic. The lengthiest of the book’s three sections, Part Two, consists of 55 interviews Northrup conducted with Dollar Baby filmmakers over a seven-year period beginning in 2013. Each is presented in chronological order by the “original date of that interview” (121), rather than using the interviews to explore bigger ideas in filmmaking, such as technology and its impact on the short film medium, the importance of pacing, or condensing and reframing adapted stories as universal. The interviews offer little insight beyond fanboy questioning akin to “how do you get your ideas.” The questions he asks the filmmakers are repetitive. Asking the different filmmakers “what attracted you most to” the Stephen King short story you chose or “how do you handle the pressure to keep the fans happy” yield replies that inadvertently become homogeneous. Again, drawing back to the largest flaw in the book — without seeing the movies beforehand, the answers become abstract. Since the interviews are available online, Northrup could have simply given links where to find them and written more narrowly focused profiles on each. These interviews did not need to be in-depth like the ones in Hitchcock by Francois Truffaut (1966), where the perception of the famous director would be cemented as a master of the medium and true auteur, or those in Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (2008), which conversely demythologized the subject from icon back to filmmaker. While the aforementioned works are written by an acclaimed filmmaker and film critic, respectively, Northrup never affects himself as an elite connoisseur; instead, he openly admits he “wrote [the] book as a fan for the fans” (555).

The book’s third section, the shortest at 29 pages (excluding its acknowledgments and dedications), fills the reader in on what 41 of the profiled filmmakers have done since creating their Dollar Babies. While the penultimate question asked in each interview for Part Two is “what’s next” for the filmmakers, the responses here feel more concentrated despite some being little more than a paragraph. For myself — someone who could never be described as a Stephen King fanatic, this is where the book came to life. But despite his clear and deep passion for the topic, the book’s numerous shortcomings make it unappealing to all but the most ardent of film festival supporters who happen to also be diehard Stephen King fans. Here’s hoping Northup takes his time on a follow-up that would make King proud.

Author Biography

Constantine Frangos is currently an undergraduate student studying English and History at Rutgers University – Camden. He is also a programmer for the yearly Reel East Film Festival.

Book Details

Stephen King – Dollar Baby: the Book, Northrup, Anthony, ed. (2021)

Albany, GA: BearManor Media, 576pp., ISBN: 978-1629336695 (hbk), $43.00