Through precise filmic techniques, Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream tragically depicts the destructive nature of addiction, particularly for the character Marion Silver (Jennifer Connelly). When read against the grain, the film’s use of lighting, mise-en-scene, and camerawork highlight the consequences of drug addiction to symbolize the disillusionment of the American Dream, revealing how Marion’s desires for success are inhibited by unattainable ideals.

In Requiem for a Dream, Marion Silver and Harry Goldfarb (Jared Leto) are a young couple who share the desire for a better life. Their relationship and its ultimate collapse illustrate how a promising and loving connection can collapse along the path of achieving the “American Dream.” Marion has a deep desire to start a fashion company, which is revealed by showing several of her drawings of dresses throughout the film. As her drug use worsens throughout the film, her career ambitions fade into the background.

Harry feels as if he’s let down his widowed mother—Sarah Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn)—by his failure to obtain a strong career and marriage. In their pursuit of happiness, Harry and Marion’s increased reliance on heroin deteriorates their plans for success and personal connection. While Marion and Harry’s lives and relationship initially appear hopeful, it becomes apparent that the couple will not be able to reconcile their love for each other and desire for success with their growing drug dependencies.

While drug addiction takes center stage, filmic techniques such as mise-en-scène, lighting, camera work, and correspondences between two key scenes emphasize the unattainability of the “American Dream” in the pair’s deteriorating relationship. The first scene (14:49) begins by presenting Marion and Harry in a calm and intimate moment on a couch together in Harry’s apartment. A high angle dolly shot of Marion and Harry emphasizes their emotional connection by drawing the viewer into their shared space through a slow zoom-in (15:10), creating an atmosphere of vulnerability that mirrors their emotional intimacy.

Additionally, there is warm key lighting on Marion and Harry while the rest of the apartment room is shaded in bleak, dull green fill and back lighting. This effect separates Marion and Harry from the drabness of the room as a hopeful icon of love and possibility, reflecting hope in their economic and personal futures. The key lighting depicts the intimate moment as a temporary symbol of love and safety surrounded by an indifferent and ugly world, perhaps signifying the “American Dream’s” ideal.

The shot transitions into a cowboy shot after the zoom-in occurs, centering the viewer of the peaceful moment of rest being shared. The camera stays still for five seconds, emphasizing the safety of this moment while the two are wrapped in each other’s arms. In this moment, the couple are safe and content despite their lack of economic success, something they chase throughout the film. The absence of diegetic sound reflects a dreamlike atmosphere of calmness, perhaps even suggesting that this moment of connection is unrealistic and a product of fiction—paralleling the elusive nature of the “American Dream.” The only sound is non-diegetic organ music, creating a foreboding sense that this calm moment is fleeting and foreshadowing their relationship’s eventual collapse, echoing the collapse of their hope for future success.

As their lives and addictions worsen, Marion and Harry’s relationship is torn apart while they attempt to achieve financial security and obtain drugs through dangerous drug deals and prostitution. In one of several bleak moments of desperation, Marion—feeling deserted—sleeps with an ex-boyfriend in exchange for heroin (59:00), while Harry drives to Florida in search of drugs, detailing the corruption at play in their pursuit of happiness.

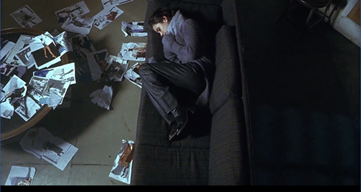

Later in the film (1:35:33), the scene revisits Marion alone on the couch, paralleling the earlier couch scene. The scene begins with an intimate choke shot of a crying Marion and zooms out to a high angle dolly shot (1:35:51), contrasting how the earlier scene began with a high angle dolly shot and ended with a choke shot. The reversal illustrates how Marion’s descent into addiction has replaced her emotional connection with Harry. This claim is supported as the first scene zoomed in on their love, ignoring the drab apartment room and its contents, to emphasize their emotional connection.

In contrast, the last scene zoomed out from Marion’s face onto the greater room, emphasizing her emotional emptiness and isolation. In doing so, the reversal highlights the devastating toll Marion’s pursuit of the “American Dream” has taken on her, leaving her alone and without hope for the life she desired. The zoom-in scene draws the viewer into an intimate moment, mimicking the idealized, story-like quality of the American Dream. Dissimilarly, the zoom-out scene disrupts this sense of intimacy by replacing the image of love with a starkly depressing image of loss, paralleling the collapse of the dream.

The key lighting and camera linger on Marion’s face, contrasting her earlier peaceful moment with Harry with her now frantic, and perhaps high, appearance, highlighting the permanence or reality of the current scene. After the slow zoom-out, Marion pulls a bag of heroin from her pocket and clutches it, almost protectively, to her chest in a heartbreakingly similar fashion to how she held Harry in the earlier scene. This visual parallel illustrates how Marion has replaced her connection with Harry with drugs, which have become her new source of comfort, assurance, and perhaps even love. Harry’s absence symbolizes Marion’s disillusionment with the American Dream and her loss of hope for a better future as well as her increasing desire for destructive escapes, such as heroin use.

Beside the couch, dozens of Marion’s sketches of clothing and fashion magazines sprawl across the floor. Many of the sketches are crumpled, clearly having been stepped on recklessly. The scene highlights Marion’s prioritization of the relief or escape offered by drugs over hopes for success through the lighting, which is keyed on Marion while the magazines and drawings are dimly lit. Notably, the lighting in the first couch scene is much warmer than the second, in which the dim lighting conveys a sense of isolation and a loss of hope.

The loss of Harry in favor of the bag of heroin critiques materialism in place of human connection, a primary myth of the American Dream. The film suggests that the dreams of success can so easily be twisted, motivating destructive behavior. The eventual destruction of protagonists’ lives, all of which are presented hopefully in the first act, details the illusory nature of the American Dream. The potentially destructive consequences of the pursuit of dreams is signified by the role of narcotic use within the film, which serves as a method to escape reality. Through lighting, mise-en-scène, and camerawork, the film ultimately suggests that the pursuit of the American dream—rooted in materialism and illusion—leads not to economic and emotional well-being but to destruction and isolation.

Reference

Aronofsky, Darren, director. Requiem for a Dream. Artisan Entertainment, 2000.

Author Biography

Ezra Minard is a first-year student at Davidson College who has an interest in English, although he currently remains undecided. In addition to his academic pursuits, he competes for the Davidson College Cross Country and Track teams. Ezra also contributes as a writer and editor for Libertas, the college’s creative writing magazine.