Uptown Girls is a 2003 romantic comedy in which a New York City socialite, Molly Gunn (played by Brittany Murphy), loses her fortune and is forced into regular employment as a nanny for an uptight little girl named Ray (played by Dakota Fanning). While Uptown Girls is a fun and heartful story of female friendship, aging, and grief, it is not always seen as such. The film’s Rotten Tomatoes reviews suggest it is difficult for many critics to fathom a woman experiencing meaningful grief. It received a 13% Rotten Tomatoes score, with many reviewers taking issue with the “whimsy” and “girlishness” of the film. One review by Geoff Pevere reads: “Can two over-pampered but fundamentally lonely persons of the blonde female persuasion bond meaningfully with each other while shopping?”

This rhetorical question is both factually unsound and revealing. Ironically, the two are never actually pictured shopping in the film. While there is nothing inherently wrong with women bonding while shopping, the reviewer’s inaccurate use of that trope to belittle the characters is worth questioning. It exemplifies how critics have weaponized the stereotypically feminine to downplay the film’s emotional resonance.

I argue that this rhetoric surrounding the film is misogynistic and minimizes honest conversations surrounding complex grief and the various ways it manifests in young women. Because Molly’s parents died when she was young, and Ray has an absent mother and dying father throughout the film, the two are connected by a sense of loss and abandonment. While Pevere acknowledges this briefly by commenting on their fundamental loneliness, he and many other reviewers trivialize and dismiss the characters’ experiences, citing the use of stereotypical characteristics of early 2000s “chick flicks” to render the experiences of the young women unserious. Despite Molly and Ray’s noticeable differences, Molly is impulsive and carefree, while Ray is rigid and hyper-mature, they form an unlikely friendship over the course of the film. Their relationship begins with conflict and resistance, but slowly, grief becomes a shared language through which they begin to connect.

While the two characters never shop together, they bond and help one another cope with their respective losses in more profound ways. For example, when Ray’s father dies, she is overwhelmed with grief and runs away to Coney Island. She does this because Molly had previously shared that she, too, ran away to Coney Island when her parents died. She says:

I wasn’t mad Ray, I was confused. Everyone was talking to me, and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying, and their voices became a blur… I knew I had to run away. So, I packed my knapsack, got on the train, looked up at the map, and decided I wanted to live in Coney Island…. The teacups were the only ride they would let me on by myself. So, I got on it and started spinning myself round and round, and I feel like I’m still there (58:37).

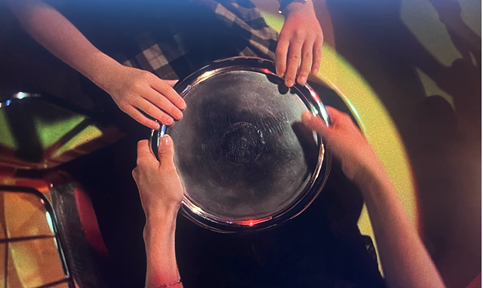

Therefore, when informed of Ray’s status as missing, Molly knew where to look. In the next scene, we see Ray and Molly together in a spinning teacup (1:18:48). Molly silently joins Ray, and the high-angle shot of their hands spinning the center disk together (1:19:07) conveys mutual understanding and vulnerability (Figures 1 and 2). This shot calls back Molly’s earlier comparison of her grief and confusion to the dizzying experience of riding the teacup, implying that while the two may experience grief differently, they are no longer alone in it.

Another example of this type of dismissiveness can be seen in Ty Burr’s review (Boston Globe), where he writes that director Boaz Yakin “keeps shying from the darker material like a studio-trained racehorse, heading for the safer turf of slapstick and schmaltz.” This framing suggests that grief must be expressed in traditionally “dark,” gritty, or overtly tragic ways to be considered legitimate. But Uptown Girls explores grief through whimsy, care, and relational healing, modes that are often dismissed as unserious because they are gendered as feminine. When grief does not conform to the traditional, often masculinized narratives of pain and instead engages with the emotional richness of female friendship, its authenticity is questioned.

The film’s articulation of grief in young women transcends the shallow, superficial judgments cast by critics who fail to see beyond their own gendered biases. Film reviewers like Geoff Pevere trivialize the emotional complexity of the characters’ experiences, reducing their grief to something inconsequential and dismissible. This critique reflects a broader societal tendency to ignore a woman’s ability to contain multitudes if she is presented within the stereotypically feminine. I argue that the emotional resonance of the film is lost on these critics due to their inability to see beyond misogynistic notions of what women’s grief should look like. They miss a powerful narrative about healing and mutual understanding that Uptown Girls offers.

References

“Uptown Girls – Movie Reviews.” Rotten Tomatoes, www.rottentomatoes.com/m/uptown_girls/reviews?type=top_critics. Accessed 1 Apr. 2025.

Yakin, Boaz, director. Uptown Girls. MGM, 2003.

Author Biography

Mia Mattern is from western North Carolina and is currently a first-year student at Davidson College, where she studies English and Environmental Studies.