Despite its screening at Cannes, status in the Criterion Collection, and ranking in Sight and Sound‘s greatest films list, Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1973) is often subject to Western readings that frame its nonlinear narrative as “difficult.” When I first encountered the film in a Parisian film studies class, classmates dismissed it as inaccessible—a reaction revealing how Hollywood-conditioned viewers misread Mambéty’s decolonial form. Critical responses beyond the classroom similarly position it as obscure or derivative, with some even comparing it to Tarantino, who emerged decades later. These readings exemplify what scholar Manthia Diawara terms “the colonial viewer syndrome”: the imposition of Western narrative expectations on films that reject them.

To me, what mainstream audiences consider challenging about Touki Bouki represents not artistic failure but decolonial strategy—a postcolonial aesthetic demanding participatory engagement. This resistance to passive consumption offers a necessary alternative to algorithms that curate viewing habits and standardize storytelling.

The Politics of Fragmentation

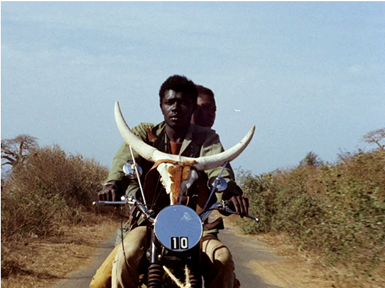

Mambéty’s nonlinear structure is a decolonial exercise. The film’s circularity—bookended by identical shots of Mory’s motorcycle, first brimming with the promise of a Parisian dream, later stripped of hope—doesn’t merely reject the three-act structure; it visualizes neocolonial entrapment. The slaughterhouse sequences, with graphic matches between dying bulls and Mory’s bike, actualize Frantz Fanon’s “Manichaean world,” where colonial mobility depends on violence.

Mambéty’s slaughterhouse sequences, with graphic matches between dying bulls and Mory’s bike, actualize Fanon’s “Manichaean world,” where colonial mobility depends on violence.

Semiotics of Resistance

What Western audiences labeled disorienting represents Mambéty’s deconstruction of traditional visual languages. This isn’t stylistic indulgence but an intervention on the theoretical level. The bull motif that threads throughout the film is a direct construction of the fate of colonized nations: when alive, the proud animal led to slaughter mirrors pre-colonial autonomy; once slaughtered, the processed carcass represents colonial extraction of resources; finally reconstructed, its horns welded to Mory’s bike, it embodies neocolonial hybrid identity. Mambaety speaks to us about the postcolonial condition through his cinematic language.

Josephine Baker’s “Paris, Paris” isn’t an ambient soundtrack or annoyance—its lyrics (“My two loves are Paris and my homeland”) illustrate the central dialectic. An almost Stockholm-like love for Parisian culture. As a Haitian man, I found my existence in Paris as the dreams of my ancestors and the nightmare of their oppressors. As I sit at a cafe and the French serve me sugar with my coffee, I think about where they got their sugar. For every grain of sugar I pour, 100 of us passed. And if you think I’m joking, there are anywhere from 4000-8000 grains of sugar in a packet, and an estimated 1 million Haitians died in slavery to the French. I feel as though I’m not supposed to love France or French culture as much as I do.

The more I learn, the more my view changes. The flow of blood and sugar extends to the city itself. The Eiffel Tower was built using “extra” money the French government had stolen from Haiti as repayment for Haiti gaining independence. The descendants of enslavers served me sugar in a city built with stolen wealth. My existence and love for Paris is paradoxical in its truest form, Stockholm-like. In the film, Mambéty denies us a Parisian payoff, the characters never leaving their home country. He doesn’t withhold resolution, he rejects the very premise that Europe represents salvation.

Cinematic Decolonization

In an era where streaming platforms privilege digestibility, Touki Bouki‘s refusal of passive consumption becomes radical. The film doesn’t need “defending”—it demands viewers willing to sit with discomfort, decipher symbolism, and unlearn colonial frameworks. Its fragmentation resists mindless consumption; its violence demands contemplation. Engaging with Touki Bouki trains audiences to interact with Global cinema beyond extractive hierarchies. Dismissing it as “difficult” mistakes its demolition of colonial narratives for formal failure. Fifty years after Senegal’s independence, Mambéty’s visual politics offer not just an alternative but a mode of resistance—challenging why certain narratives are deemed “accessible” and redefining cinematic greatness in a Hollywood-dominated landscape.

References

Diawara, Manthia. African Cinema: Politics & Culture. Indiana UP, 1992.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox, Grove Press, 2004.

“Josephine Baker -‘Paris, Paris’ Lyrics.” LyricsTranslate, 1930, lyricstranslate.com/en/paris-paris-paris-paris.html.

Mambéty, Djibril Diop, director. Touki Bouki. Kino Lorber, 1973.

Mambéty, Djibril Diop, director. Hyènes. Performance by Ami Diakhate, Kino International, 1992.6.

“Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time 2022.” British Film Institute, 2022, www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/greatest-films-all-time.

Author Biography

Miles Hart is a Haitian-American photographer, filmmaker, and writer at the University of Chicago. He is a third-year Economics major and Cinema & Media Studies minor. This piece analyzes decolonial aesthetics in global cinema and explores postcolonial identity in different mediums.