Even before studying film, I had always been at least dimly aware of Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994). It is a film embedded so deeply into our collective cultural consciousness that not encountering it in one way or another is essentially impossible. Having won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay in 1995, being the top-grossing film at the US box office its first weekend, and with an average rating of 4.3 on Letterboxd, Pulp Fiction is clearly regarded highly by critics and the public alike. After watching the film myself, however, I found that it fell short of these high expectations. Instead of coming out on the other side completely changed, I was left instead with a feeling of overwhelming indifference.

My biggest issue with Pulp Fiction is how difficult it is to connect with the characters. The actors all give strong performances, and Tarantino’s characters certainly have the potential to be interesting, but that potential is as far as that intrigue goes. In the film’s closing sequence, the audience is met with the sense that this is meant to be a turning point for Jules, particularly when he repeats the famous Ezekiel 25:17 line:

“The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. […] And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers, and you will know I am the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon you.”

In reflecting on this line and seemingly walking away from a life of crime, Jules supposedly grows as a character. However, the audience is never shown what drives him, minimising the chance that a given spectator will care about this change. Although I understand that part of the film’s cleverness stems from its fragmentation, from its stories unexpectedly overlapping and being left incomplete, this does little to change the fact that it feels near impossible to care about Jules’s growth. This is not a general criticism of Tarantino’s skill for writing. In Kill Bill: Volume 1, we do not even learn the protagonist’s name, and yet it is easy to align with her, as the audience is shown the motivations behind her actions. It seems that this distance between character and spectator is a symptom of Pulp Fiction alone.

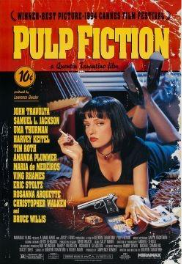

A secondary aspect of the film that I take issue with concerns the depiction of women. Time and again, Pulp Fiction is praised for being subversive, and this partly true regarding its women, such as Honey Bunny being an active, gun-wielding maniac. Beyond that, however, I struggle to see where the film upends stereotypes of femininity. Fabienne is consistently infantilised, relying heavily on Butch for security and reassurance, which is uncomfortable at best to watch. Where there might be room for contention is in the depiction of Mia. Newman (137) refers to Mia as “the only woman of much consequence in the film,” arguing that the film poster (Figure 2) and trailer “make clear that her role is to be an object of desire, but also suggests some agency for Mia as a powerful or seductive woman who uses her femininity.” I can concede that Mia is different to an extent, as she is not directly sexualized by way of male-gaze-centric cinematography. There are no stereotypical lingering close ups and glamour shots of her. However, her costuming and enigmatic qualities alluding to the femme fatale archetype remind us that she primarily exists to be attractive to Vincent. Her femininity is only used to serve men rather than herself, which is not overwhelmingly empowering. Although there are other elements of Pulp Fiction that can definitely be called subversive, this innovation seems to end where its women are concerned.

To give credit where credit is due, Pulp Fiction is structurally intriguing. Playing with temporality and fragmented narratives demonstrates intricacy and intentionality for which I have to applaud Tarantino. The colloquial dialogue and the film’s soundtrack are also features of Pulp Fiction that I genuinely like. However, the complex narrative structure is not enough to save the characters from being difficult to root for. Although I appreciate certain aspects of this film and how it experiments with the medium, I simply cannot bring myself to care for Pulp Fiction beyond that.

Reference

Newman, Michael Z., “Say ‘Pulp Fiction’ One More Goddamn Time: Quotation Culture and an Internet-Age Classic.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 2014, pp.125-142, doi: 10.1080/17400309.2013.861174.

Author Biography

Annie-Faith Obed is a student at the University of Birmingham.