Over 20 years after its initial release, Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s film Taste of Cherry (1997), an essential piece of cinematic civil service, still stands as a vital contemplation on the wearying yet worthwhile act of living. It calls attention to the beautiful intricacies of everyday life while also elevating the struggles that come with day-to-day mundanity in a manner similar to Italian Neorealist films of the 1940s. However, the latent uncertainty of Cherry’s protagonist furthers the film’s vision of delicate hopefulness through his curious one-off interactions with a diverse handful of Tehrani men whom he attempts to recruit in his suicide mission. Each offers his own particular insights into why they will or won’t help Mr. Badii, ultimately giving viewers a contemplative crash course on how to revel in the simplistic beauties of human nature. From a benign and innocent young Tehrani soldier to a dedicated priest-in-training from Afghanistan, Mr. Badii’s inquisitive encounters with others take time to soften his morbid determination.

Not until a nameless taxidermist offers kindly words of wisdom about the sheer gravity of a simple mulberry tree do we see true doubt start to form behind Mr. Badii’s once-spiritless eyes. Hope might live within him now through a newfound connection between the perseverance of existence and the perpetual resilience of the natural world around him. Kiarostami’s close audiovisual scrutiny of environmental nature and human nature explores the ways in which these two entities influence and rely upon each other for coexistence.

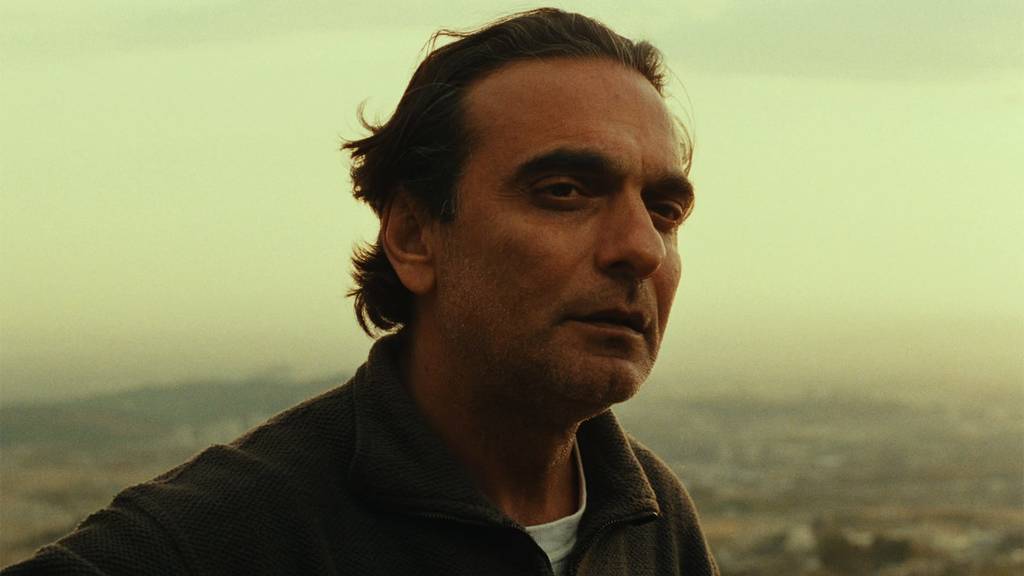

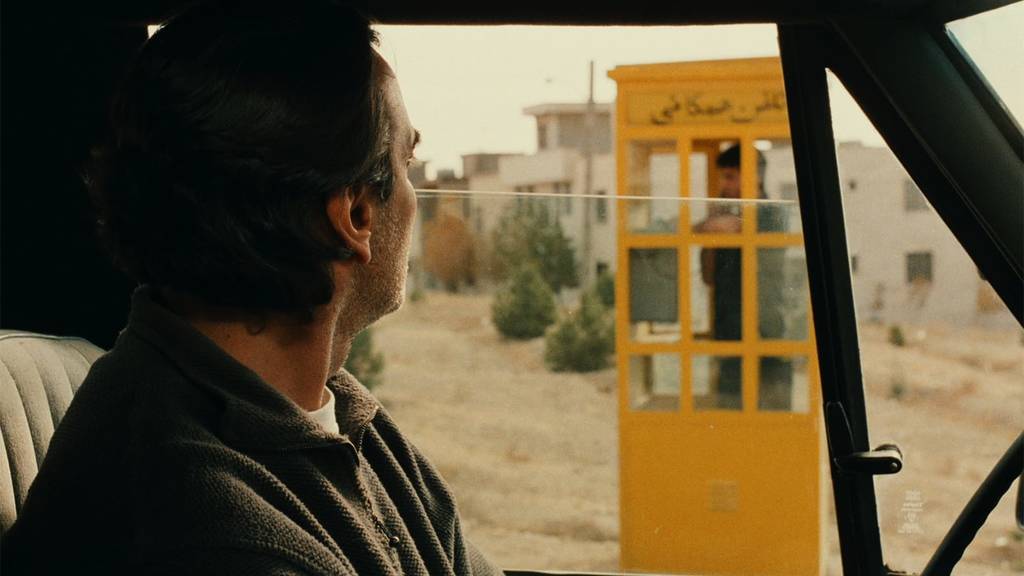

The gentle stylization of the setting perhaps proves more distinct and impressive than any other cinematic aspect in this minimalist gem. Cherry takes place in Tehran, and the mountainous Iranian landscape filled with viridescent oases imposes upon Mr. Badii’s mission of self-destruction. Wide, establishing landscape shots not only uplift the film’s richly tranquil appearance (allowing the audience to absorb its beauty) but also cast the land as parallel to the film’s heavy concepts of life and death. This land is lush, yet quiet and inert; almost completely at rest and yet bursting with life just under the surface. Although initially appearing lifeless, the land nevertheless thrives in its own subtlety, flourishing with a life of its own amidst its gentle nature. Mr. Badii, although planning to commit suicide and leave the world, still finds a way to connect with the land by choosing to be buried after his death. Perhaps he possesses a reluctance to let go completely, and we, the audience, perceive this reluctance through the immense power Kiarostami gives to the exquisite Iranian land.

Cherry’s dedication to realism provides a welcome reprieve from the age of the computer-generated action blockbuster—the film feels so deeply genuine that it is easy to forget that Kiarostami’s universe is a fabricated one. Kiarostami balances the emotional interiority of his protagonist with the openness of the Tehrani landscape surrounding him, creating a deeply believable world which feels at once unknowably vast and intimately focused. Furthermore, Cherry’s minimalist sound design, affinity for long takes, and intimately close-scale shots ensure that nothing distracts its audience from the interactions playing out onscreen and the emotions which those interactions evoke.

Since its 1997 release, Taste of Cherry has entertained a split reception among viewers and critics alike. Many have praised the picture as a masterpiece of minimalist cinema—in fact, after its release at Cannes, Cherry became the first Iranian film to win the Palme d’Or. Others, however, have argued that Taste of Cherry’s slow pacing and lack of initial exposition give rise to a disengaging and ultimately boring viewing experience. Roger Ebert describes the film as “a lifeless drone,” arguing that viewers cannot possibly sympathize with Mr. Badii without knowing “anything at all about him.” Yet how can viewers be expected to bond with Mr. Badii if they know everything there is to know about him from the film’s outset?

Taste of Cherry’s realism thrives precisely in its ambiguity, its control of how much information it reveals and conceals from its viewers. Ebert is correct in his claim that Cherry is not particularly exciting, but he seems not to understand that the film is not intended to be action-packed or attention-grabbing. Cherry stands tallest as an exercise in introspection, a meditation on life and reasons for living. It demands patience and consideration from its viewers in order to be fully experienced and appreciated. To this end, Kiarostami feeds exposition to his audience in gradual, minute mouthfuls, keeping them engaged with the film’s world despite the slow pacing of its narrative. In fact, for the first twenty minutes of the film, viewers possess no more knowledge of Mr. Badii’s plan than do his passengers, wondering alongside them as to his intentions. In effect, the audience becomes simply another passenger hitching a ride in Mr. Badii’s vehicle, a sensation reinforced by Cherry’s intimate, point-of-view camerawork.

Even the lines of fiction and reality become blurred in the film’s conclusion—Mr. Badii lies in his grave, gazing at the moon above him as the screen fades to black, leaving us to desperately ponder his fate. Suddenly, the dark screen cuts to footage of the film’s production, promptly shattering the hyper-realistic world cultivated over the past hour and a half as actor Homayoun Ershadi offers director Abbas Kiarostami a cigarette. Kiarostami denies viewers not only the closure of knowing Mr. Badii’s fate but also the security of the film’s established universe. The seemingly insipid nature of Cherry might not warrant complete investment throughout its run, yet by the time we arrive at the film’s unorthodox ending (accompanied by Louis Armstrong’s trumpet-heavy recording of “St. Infirmary Blues”), our attentiveness awakens with each stately note of the brass instrument. As Cherry’s only nondiegetic sound, Armstrong’s stirring trumpet piece asks us to reflect on each moment of the film, possibly inclining us to return for a second viewing that will uplift Kiarostami’s work even further. Subsequently, this bonus footage stands as Kiarostami’s open acknowledgment that the world and characters he has created are fictional; however, rather than invalidating the film’s exploration of hard realities, the final footage allows viewers to feel mesmerized by the film’s impressively fabricated realism.

Criterion’s newly released Blu-Ray edition of Taste of Cherry comes packaged with an afterword by A. S. Hamrah, wherein the critic revisits one of Kiarostami’s most iconic works in the wake of his death in 2016. In this piece, Hamrah praises both Kiarostami’s cinematographic and thematic choices and Ershadi’s compelling performance. Hamrah also ponders the implications of Cherry’s ending, defending the clip’s inclusion from those who call it a cop-out. The Blu-Ray disc itself features four additional videos, including commentary and analysis from film scholars Hamid Naficy and Kristin Thompson, footage from the film’s production, and an interview with Abbas Kiarostami himself. These videos can also be found on the Criterion Channel website, available to members with a subscription. While not essential viewing to appreciate Taste of Cherry as a film (indeed, their inclusion feels somewhat contradictory to the carefully-crafted realism and simplicity of the film’s universe), these videos provide ample background information for those interested in Kiarostami’s filmmaking process, motivations, and ambitions both during and after Cherry’s production. In Kiarostami’s interview in particular, the director details his creative process, his experiences with censorship, and his goals in filmmaking. Kiarostami credits the human imagination as a core influence on his work, one which palpably shines through in Taste of Cherry—the film reminds us to appreciate rather than forget life’s most basic pleasures, like that of the sweet cherry, so that we may imagine an even sweeter taste of our own creation to anticipate in this fleeting yet eternal lifetime.

For more information about this Criterion title, please visit: https://www.criterion.com/films/242-taste-of-cherry