Stress is a universal thing. Everyone’s been overwhelmed by something at some point in their life, and the anxiety it produces can make it feel like the universe is conspiring against you. This is an unpleasant experience in everyday life, yet there are many stories out there dedicated to inducing this sensation of dread and panic in the viewer. Perhaps audiences crave catharsis in their storytelling, since most of these films feature a climax dedicated to giving viewers quite the cathartic experience.

Here is a festival dedicated to stressful viewing, with five films which showcase that familiar feeling of all-encompassing distress and collapse. Those films are The Stalking Moon (Mulligan, 1968), Sorcerer (Friedkin, 1977), Uncut Gems (Safdie, 2019), Phone Booth (Schumacher, 2002), and All That Jazz (Fosse, 1979).

We’ll start with intense silence. In Robert Mulligan’s western The Stalking Moon, Gregory Peck plays retiring army scout Sam Verner, who decides to help a former Apache captive named Sarah (Eva Marie Saint) and her son (Noland Clay) build a new life. His efforts are interrupted by Salvaje, the boy’s deadly father (Nathaniel Narcisco), hunting the group down and trapping them in Verner’s cabin, intent on taking the kid back and killing everyone else. The film becomes a deadly game of cat-and-mouse between Verner and Salvaje, utilizing long periods of silence to build tension. The best example of this is near the climax. Sam is falling asleep in his cabin when he hears a noise coming from the storeroom. Realizing that Salvaje has entered the building, he snuffs out the lights and readies himself. Mulligan utilizes closeups and wide, POV shots to build suspense, until Salvaje finally enters the room. This ultimately leads into the climax, a ten-minute stalking and fight sequence between Verner and Salvaje – which is made all the more stressful once Sam is stabbed in an artery and has to manage a tourniquet. And while Salvaje is defeated in the end, the film ends with Sam still bleeding as he crawls back to the cabin – leaving the audience worried even as the credits roll.

The next film in the festival is an explosive ride. William Friedkin’s Sorcerer is a white-knuckle thriller about four desperate men – Scanlon/“Dominguez,” Manzon/“Serrano,” Kassem, and Nilo (played by Roy Scheider, Bruno Cremer, Amidou, and Francisco Rabal) – transporting unstable nitroglycerin over two-hundred miles in ramshackle trucks. Friedkin brings a cinema verité approach to the material, giving it a feeling of realism and authenticity that greatly enhances the film’s ability to create tension. The scenes where each truck must cross a river in the middle of a horrible storm by driving over a flimsy bridge is nerve-wracking. The bridge, which is only a bunch of logs held loosely together, wobbles and tilts precariously – the trucks come dangerously close to spilling over into the river. Then there is the fact that one of the two drivers for each truck needs to walk in front of the vehicle and guide them through a downpour – which nearly kills Kassem when he breaks a log, falls into the river, and is almost run over by Manzon before he can get the driver’s attention. Over the course of the film the many hellish events the drivers go through take their toll. When they find the only road blocked by a giant felled tree, Scanlon freaks out – he collapses and strikes the ground, then futilely attempts to hack a new path through a swamp before breaking down and crying. At no point in the runtime does the film let the audience relax, either – one such moment, where two characters calm down and start getting to know each other better, ends with a tire blowing out and the nitro exploding, killing them. This is a nervous, anxious film that wants the audience to be on the edge of their seats from start to finish.

Similarly, the Safdie brothers’ 2019 film Uncut Gems is a relentless, anxiety-inducing tale. Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler), a jewelry store owner in New York City, has a lot of problems. His marriage is collapsing, he owes debts to everyone (who are all coming to collect), and Kevin Garnett won’t return the black opal Ratner loaned to him before the date of an auction where Ratner hopes to sell the thing. His biggest problem, however, is his impulsive need to gamble. The Safdies direct the film in a claustrophobic, chaotic style that accentuates the turbulent situations Howard continues to get himself into. The insanity on display in a few scenes also helps – note the scene where, while trying to get the black opal back, everything in the world goes wrong. He is constantly being called by people with wildly different goals, Kevin Garnett is stuck in the man trap of the store, a creditor comes to collect, and Howard doesn’t have a ring he owes to Garnett. So much happens in such a short amount of time that the film causes sensory overload. It is an unbelievably stressful narrative and the Safdie brothers flawlessly create an incredible experience that will leave any viewer breathless by the end.

In another part of New York City, we find our next movie. Joel Schumacher’s 2002 thriller Phone Booth is a masterclass in how to make one small location visually interesting and how to make a thriller set in a small box. The story is simple: sleazy publicist Stu Shepard (Colin Farrell) answers the phone in a phone booth. The voice on the phone (Kiefer Sutherland) says that if Stu hangs up, then the caller will kill Stu (and he backs it up by loudly cocking a rifle after Stu doubts him, and shoots a toy robot next to the booth). From there the film goes into a frenzied, harrowing series of events, all in or around the booth, that will change Stu’s life forever. This real-time thriller, which features some incredible use of the camera and clever split-screen editing, is one of Schumacher’s best films. Farrell’s desperate, panicked performance provides a constant source of anxious energy across the film’s runtime. The film remains planted in Stu’s perspective most of the time, locking the audience into his point of view during horrible acts – at one point a pimp tries to break into the booth and drag Stu out (which makes the caller kill the pimp and leads to the police surrounding the booth), the caller shoots Stu in the ear when he tries using a cell phone to call for help, and eventually Stu’s wife shows up at the scene and is threatened by the caller. The killer has a motive – he wants Stu to confess to every horrible thing he’s ever done, and Stu’s confession is a high point in Farrell’s career. While the film ends with Stu free of the booth, the caller gets away – and tells Stu that he’ll be checking up on him from time to time.

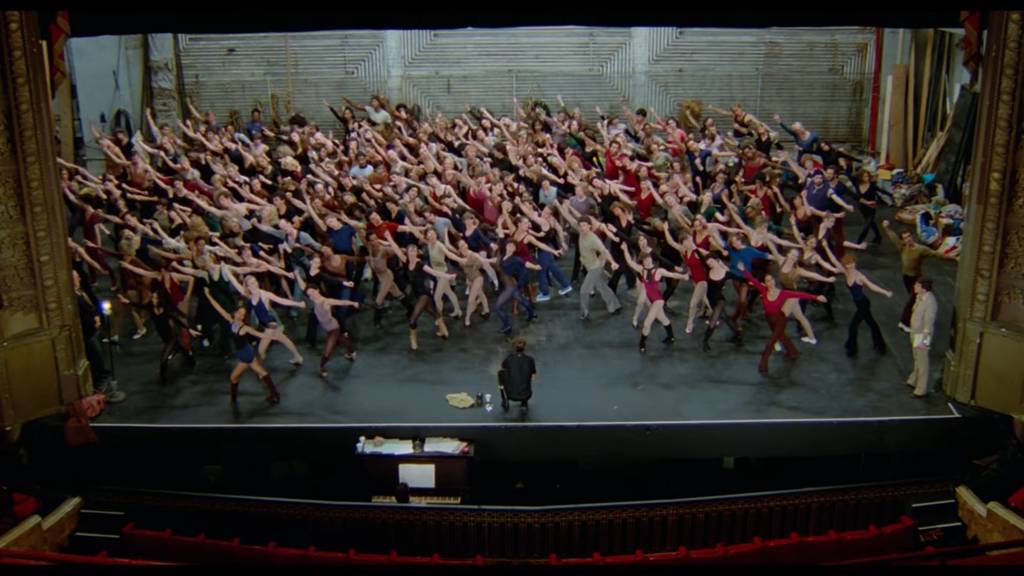

The final film of this festival is a bit more relaxed than the others, in that it’s more about working yourself to death. Bob Fosse’s 1979 musical All That Jazz is the story of Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), a Broadway and film director currently editing his latest movie while also working on the choreography for his new play. Joe is a drug-addled, chain-smoking, hypersexual mess of a man who (literally) flirts with death in fantasy sequences. In the film, Joe works himself to the point of exhaustion – he suffers a massive heart attack and has to go through surgery, and even that isn’t enough to save him. A standout scene that places the viewer straight into his perspective is the table read for the play. After the first page, all sound except for those made by Joe fade out of the film. For the next minute, as the rest of the people in the room have a wonderful time going through the play, Joe stresses over everything and can only hear minute things like the tapping of a pencil, his hand rubbing his arm, and the horrid coughing he makes every other breath. The whole film locks the viewer into Joe’s point of view in less extreme ways, showcasing “life as it is lived, perceived, and experienced through one person’s head, heart, and nervous system” (Seltzer). Indeed, the film’s climax is a giant musical number explicitly set in Joe’s mind as he dies, with everyone and everything reflecting how he sees the world and himself. All That Jazz is a masterpiece of film, and if you have ever felt like you’re working yourself into an early grave you will feel uncomfortably sympathetic to Joe’s plight.

These films all showcase stressful situations and characters dealing with them in various ways. Some of them are bleak, some of them end with a ray of hope, but all of them can make a viewer feel anxious. They are fascinating examples of how a universal experience can be interpreted and represented differently across genres and by wildly different creative teams.

Author Biography

Yaakov “Jacob” Smith is a student in the University of North Carolina’s Film Studies program. He aspires to be a movie director one day and hopes to continue his studies through graduate school. When he is not studying movies, he dabbles in photography and creative writing, and reads novels.

References

All That Jazz. Directed by Bob Fosse, 20th Century Fox, 1979.

Phone Booth. Directed by Joel Schumacher, 20th Century Fox, 2002.

Seltzer, Alvin J. “All that Jazz : Bob Fosse’s Solipsistic Masterpiece.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 1, 1996, pp. 99-104. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/all-that-jazz-bob-fosses-solipsistic-masterpiece/docview/226991878/se-2?accountid=14606.

Sorcerer. Directed by William Friedkin, Universal Pictures and Paramount Pictures, 1977.

The Stalking Moon. Directed by Robert Mulligan, National General Pictures, 1968.

Uncut Gems. Directed by Josh Safdie and Benny Safdie, A24, 2019.