During my senior year of undergrad, I was assigned to peer review papers for a film studies class I was taking. Usually, this process is pretty uneventful, with the biggest offense typically amounting to a couple of comma splices and a sentence fragment here or there. This time, however, I was baffled by what I read. Around halfway through the text, the author vividly described a violent rape scene while paradoxically suggesting the rapist’s actions were justified. Reading the paper from start to finish made me wildly uncomfortable, but what turned my stomach even more was the barely occupied bibliography with only a few sources– all written by white men. At this discovery, I became defeated and angry. It was hard to imagine that someone could detail a topic so horrific and intrusive without even considering a female perspective.

Coincidentally, it was during this time that I encountered the concept of citation ethics, which pertains to the ethical and equitable treatment of academic sources, with a specific focus on fostering diversity and inclusion. I must admit that this newfound knowledge is what prompted me to delve into the author’s bibliography, a section of the paper I had rarely visited or contemplated before. Although I had been taught about source credibility, distinguishing primary from secondary sources, and similar concepts from a young age, source diversity had not been at the forefront of my consciousness until more recently. This realization made me question whether a lack of education contributed to my negative peer-reviewing experience. If citation ethics were still new to me, it was plausible to consider that the concept was unfamiliar to many of my peers.

Amidst this period of introspection and deep diving into the realm of citation ethics, I became increasingly intrigued by the levels at which diversity and inclusiveness were promoted and incorporated within undergraduate film studies. To gain quantitative insights into this matter, I turned to the comprehensive citational database of Film Matters Magazine (FM) compiled by M. Sellers Johnson, which documents the diversity of source authors referenced across print editions 1.1 through 13.3. In order to conduct this study, Sellers relied largely on empirical data acquired by researching writers, visiting faculty pages, assessing available photographs, and other reliable sources in which an author affirms their identity.

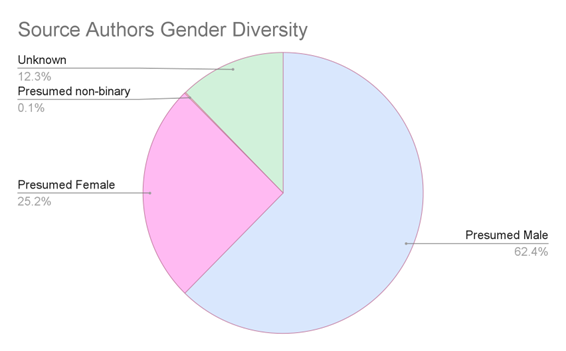

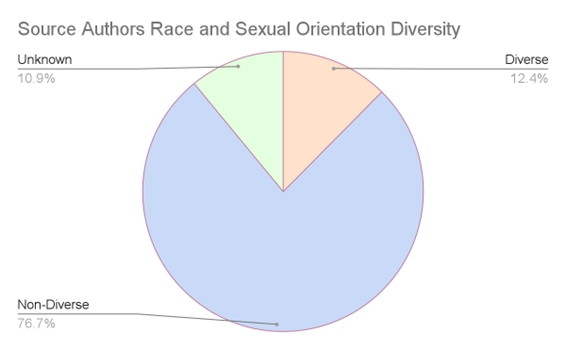

Both graphs in this article present cumulative data percentages, categorized into two sections (Figures 1 and 2). Figure 1 highlights gender diversity solely, while Figure 2 provides a comprehensive perspective by aggregating race, sexual orientation, and gender identity into “diverse” and “non-diverse” categories. It is important to note that in Figure 2, the non-diverse label refers specifically to individuals with white cis-heterosexual identities, including both men and women. On the other hand, the diverse label encompasses a range of race/ethnicities, gender identities, and sexual orientations, reflecting historically marginalized groups. If the author’s identity could not be confirmed or a source did not provide authorship information, it was appropriately designated as “unknown.”

The data starkly reveal a lack of inclusivity in the selection and citation of sources, with an overwhelming dominance of male and non-diverse voices, limiting the multifaceted range of experiences and knowledge that should be reflected in undergraduate scholarship. Out of all sources, only 25.2% are presumably female, while an almost nonexistent amount identify as non-binary. While it is plausible that the absence of non-binary representation stems from a dearth of published information on authors’ preferred pronouns—an aspect that remains relatively nascent in scholarly practices—the stark reality remains unaltered. This raises important questions about inclusivity and representation within the academic landscape, signaling a need for greater awareness and conscious efforts to diversify the sources cited in undergraduate research.

In her essay, “Citation, Erasure, and Violence: A Memoir,” anthropologist Christen Smith discusses an experience in which her work was plagiarized, stating “I felt like someone had taken something dear from me without my permission. My words, twisted yet recognizable, sat in front of me without my permission, and I felt violated” (207). In this instance, Smith was not affected by a lack of diverse perspectives, necessarily, but rather the lack of recognition of her intellectual property, demonstrating the very ways in which women of color are systematically exploited yet left largely unrecognized for their research efforts. Therefore, the issue of citation ethics extends far beyond a “scarcity” of POC, female, and gender-expansive academics and into full-fledged violence against the non-dominant voice.

Smith further delves into the topic by sharing insights from a pilot study she conducted alongside Dominique Garrett-Scott titled “We Are Not Named: Black Women and the Politics of Citation in Anthropology.” This study aimed to examine citation rates for Black women across various magazines. Remarkably, the findings mirrored those of the Film Matters citational database, revealing a pervasive lack of diversity. Smith highlights, “In that study, we found that although Black women make up about 2.6 percent of U.S. anthropologists, they represent only 1.5 percent of the total citations included in this study—82 out of 5,445” (209, 210). She goes on to emphasize the significant disparity between citation practices, stating that while only about 29 percent of non-Black authors cited Black women, “100 percent of Black authors cited Black women” (210). These findings highlight the crucial relationship between author identity and the sources they choose to incorporate

Similarly, the Film Matters citational database illuminates a relationship among authors, subjects, and scholarly citations. The data reveal that an author’s research focus may frequently coincide with their cultural identity, forming a compelling bond between the subject matter and the cited sources. For instance, when examining an essay delving into queer themes in a film, it becomes apparent that a broader spectrum of queer and gender nonconforming scholars is naturally drawn upon, given the significance of their perspectives to the study. This type of representation is crucial because topics that encompass unique cultural insights greatly benefit from the inclusion of authors who belong to those specific categories. By incorporating a more diverse array of voices, the author of the essay I peer reviewed could have enhanced the depth and inclusivity of their analysis.

Moreover, it is crucial to recognize that while researching topics related to oneself can be extremely beneficial, venturing into topics beyond one’s comfort zone or personal identity can be just as valuable and enriching, if not more so. Engaging with diverse perspectives fosters intellectual growth, empathy, and a deeper understanding of our world. However, it is crucial to approach such exploration with mindfulness and inclusivity. This means actively seeking out and incorporating diverse resources that reflect a variety of voices and experiences, even in areas that may not directly pertain to race, sexuality, or other marginalized identities. By embracing a mindful and inclusive approach across all subjects, we can challenge the default norm of white, male, and heterosexual perspectives and create a more inclusive and equitable academic discourse.

As scholars, we are responsible for defying and dismantling the structural barriers that perpetuate these inequities. We must actively seek out and amplify marginalized voices, recognize the inherent value of diverse perspectives, and critically reflect on our biases and privileges. To achieve this, educational institutions, scholarly communities, and individual researchers should prioritize training and resources that promote citation ethics and inclusive research practices. However, the solution starts with you. Following the advice of Smith’s “Cite Black Women” movement, by acknowledging underrepresented scholars, integrating their work into our research, and creating a space where all voices can be recognized, we can create a safe environment for diversity to flourish.

I began my journey into citation ethics feeling disheartened, unsure if positive change was even achievable, and if so, doubtful in my ability to advocate for it. I had fallen victim to my own complacency, believing that the world is unfair and, therefore, I should simply get used to it and move on. As I immersed myself in the study of citation ethics, however, I realized that the power to effect change doesn’t reside solely in the hands of a select few; it’s a collective endeavor open to anyone willing to challenge the status quo. It became evident that even the smallest actions, like citing diverse voices in my research or encouraging my peers to do the same, could contribute to a larger movement for inclusivity and fairness in academic discourse.

While this article may have started as a means to explore and better understand my experiences and curiosities concerning citation ethics, it has evolved into a call for action. I implore professors, scholars, and, most significantly, my peers to join this venture. While creating change can, at times, seem daunting, I want to reiterate that even the most minor actions can propel us in the right direction. So next time you’re feeling overwhelmed by the lack of inclusion in the world and within your own classrooms, give yourself the grace to feel, really feel, your emotions—whether that’s anger or dismay. Let these emotions act as catalysts for change, even if it’s something as simple as acknowledging the issue. Now, let’s move forward together. Here are some actionable steps you, as students, faculty, scholars, and beyond, can take to champion citation ethics and inclusivity in your academic journey:

- Educate Yourself: Take the time to familiarize yourself with citation ethics and the importance of uplifting underrepresented voices in your field of study. Acknowledge that this process may bring up difficult emotions.

- Engage in Dialogue: Foster open dialogues amongst your friends, classmates, and instructors about the need for diversity and the impact of inclusive scholarship. Practice active listening while ensuring that your opinions are vocalized.

- Diversify Your Sources: Make an effort to source a diverse range of voices within your own writing and research. Practice incorporating topics outside of your comfort zone.

- Advocate for Change: Encourage your academic institutions, educational communities, and professional organizations to prioritize resources and training that promote citation ethics and inclusivity.

- Self-Care: Prioritize yourself and emotional well-being. Acknowledge your emotions, if and when they arise, and seek support from friends, mentors, and your community. Remember that you’re not alone; you possess the necessary skills to enact change.

References

Bailey, Moya, and Trudy. “On Misogynoir: Citation, Erasure, and Plagiarism.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, 2018, pp. 762–768, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447395.

Bali, Maha. “Inclusive Citation: How Diverse Are Your References?” Reflecting Allowed, 8 May 2020, blog.mahabali.me/writing/inclusive-citation-how-diverse-are-your-references/. Accessed 28 Sept. 2023.

Johnson, M. Sellers. “Citation Ethics Project Update.” Film Matters, 28 July 2023, www.filmmattersmagazine.com/2023/07/25/citation-ethics-project-update-by-m-sellers-johnson/. Accessed 28 Sept. 2023.

Smith, Christen. “Citation, Erasure, and Violence: A Memoir.” American Anthropological Association, vol. 37, no. 2, 2022, https://doi.org/10.14506/ca37.2.05.

Smith, Christen A. “Our Praxis.” Cite Black Women, 2018, www.citeblackwomencollective.org/our-praxis.html.

Yong, Ed. “The Women Who Contributed to Science but Were Buried in Footnotes.” The Atlantic, 12 Feb. 2019, www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/02/womens-history-in-science-hidden-footnotes/582472/. Accessed 28 Sept. 2023.

Author Biography

Alexis Johnson is a recent Film and International Studies graduate from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. She was fascinated by the intersection between cinema and cultural identity throughout her academic journey. However, she also possesses a passion for exploring film movements often overlooked in academia. Alexis hopes to delve further into these interests by one day acquiring a master’s degree.